Acceptable Use Policies for Foundation Models

Author: Kevin Klyman

Considerations for Policymakers and Developers

Policymakers hoping to regulate foundation models have focused on preventing specific objectionable uses of AI systems, such as the creation of bioweapons, deepfakes, and child sexual abuse material. Effectively blocking these uses can be difficult in the case of foundation models as they are general-purpose technologies that in principle can be used to generate any type of content. Nevertheless, foundation model developers have been proactive in this area, adopting broad acceptable use policies that prohibit many dangerous uses that developers select themselves as part of their terms of service or model licenses.

As part of the 2023 Foundation Model Transparency Index, researchers at the Stanford Center for Research on Foundation Models cataloged the acceptable use policies of 10 leading foundation model developers. All 10 companies publicly disclose the permitted, restricted, and prohibited uses of their models, but there is little additional information available about these policies or how they are implemented. Only 3 of 10 leading foundation model developers disclose how they enforce their acceptable use policy, while only 2 of 10 give any justification to users when they enforce the policy.

This post provides background on acceptable use policies for foundation models, a preliminary analysis of 30 developers’ acceptable use policies, and a discussion of policy considerations related to developers’ attempts to restrict the use of their foundation models.

Background

What is an acceptable use policy?

Acceptable use policies are common across digital technologies. Providers of public access computers, websites, and social media platforms have long adopted acceptable use policies that articulate how their terms of service restrict what users can and cannot do with their products and services. While enforcement of these policies is uneven, restrictions on specific uses of digital technologies are widespread.

In the context of foundation model development, an acceptable use policy is a policy from a model developer that determines how a foundation model can or cannot be used.1 Acceptable use policies restrict the use of foundation models by detailing the types of content users are prohibited from generating as well as domains of prohibited use. Developers make these restrictions binding by including acceptable use policies in terms of service agreements or in licenses for their foundation models.2

Acceptable use policies typically aim to prevent users from generating content that may violate the law or otherwise cause harm. They accomplish this by listing specific subcategories of violative content and authorizing model developers to punish users who generate such content by, for example, limiting the number of queries users can issue or banning a user’s account.

Acceptable use policies relate to how foundation models are built in important ways. For example, developers frequently filter training data in order to remove content that would violate acceptable use policies. OpenAI’s technical report for GPT-4 states “We reduced the prevalence of certain kinds of content that violate our usage policies (such as inappropriate erotic content) in our pre-training dataset, and fine-tuned the model to refuse certain instructions such as direct requests for illicit advice.”3

In addition, many developers state that the purpose of reinforcement learning from human feedback (RHLF) is to make their foundation models less likely to generate outputs that would violate their acceptable use policies. Meta’s technical report for Llama 2 notes that the risks RLHF was intended to mitigate include “illicit and criminal activities (e.g., terrorism, theft, human trafficking); hateful and harmful activities (e.g., defamation, self-harm, eating disorders, discrimination); and unqualified advice (e.g., medical advice, financial advice, legal advice),” which correspond closely to the acceptable use policy in Llama 2’s license. Anthropic’s model card for Claude 3 similarly says “We developed refusals evaluations to help test the helpfulness aspect of Claude models, measuring where the model unhelpfully refuses to answer a harmless prompt, i.e. where it incorrectly categorizes a prompt as unsafe (violating our [Acceptable Use Policy]) and therefore refuses to answer.”

Distinguishing acceptable use policies from other mechanisms to control model use:

Acceptable use policies are not the only means at a developer’s disposal to restrict the use of its models. Several other policy-related mechanisms that developers implement to restrict model use include:

- Model Behavior Policy: Model behavior policies determine what a model can or cannot do. While acceptable use policies apply to user behavior, model behavior policies apply to the behavior of the model itself.4 A model behavior policy is one way of effectively embedding the acceptable use policy into the model; methods for imposing a model behavior policy include using RLHF to cause the model to be more likely to refuse violative prompts or employing a safety classifier to filter violative model outputs. Model behavior policies generally go well beyond the acceptable use policy in terms of their impact on the model; for example, many developers fine-tune their models to produce more polite responses, though they do not prohibit users from generating impolite responses.

- Model Card: Model cards, which are published alongside machine learning models when they are released, provide essential information about models such as their intended uses and out-of-scope uses. However, model cards are not enforceable contracts, and they are not generally referenced in model licenses or developers’ terms of service; as a result, these out-of-scope uses do not rise to the same level as prohibited uses in an acceptable use policy.5

- API Policy: Policies relating to application programming interfaces (APIs) determine acceptable user behavior in relation to a company’s API. These policies generally apply to more than one foundation model and differ from acceptable use policies in that they attempt to shape the actions a user takes via an API, not the content that a user elicits from a specific model.6 Enforcement of API policies differs from enforcement when users are making individual queries in a playground environment or a user interface for a chatbot—companies must consider the risk of mass generation of violative content as well as the creation of services built on top of their models that violate their policies.

- Third party contracts: Foundation model developers frequently partner with other firms to disseminate foundation models. These include cloud service providers (e.g., Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure, Google Cloud Platform), platform providers (e.g., Scale AI, Nvidia), database providers (e.g., Salesforce, Oracle), and model distributors (e.g., Together, Quora). Custom contracts with third party providers of a developer’s foundation models often include use restrictions, but the extent to which companies’ acceptable use policies are altered via these partnership agreements is unclear.7

⠀ Emerging norms among closed foundation model developers on acceptable use policies:

Although generative AI is a nascent industry, norms have begun to emerge around use restrictions for foundation models. In 2022, OpenAI, Cohere, and AI21 Labs wrote in their “Best practices for deploying language models” that organizations should “Publish usage guidelines and terms of use of LLMs in a way that prohibits material harm to individuals, communities, and society such as through spam, fraud, or astroturfing.”8 As part of the November 2023 UK AI Safety Summit, Amazon, Anthropic, Google Deepmind, Inflection, Meta, Microsoft, and OpenAI shared their policies related to “preventing and monitoring model misuse,” many of which referenced their acceptable use policies.

Limitations of acceptable use policies for foundation models:

As currently implemented, acceptable use policies for foundation models can have serious limitations. Recent research from Longpre et al. has shown that of seven major foundation model developers with acceptable use policies, none provide comprehensive exemptions for researchers. As a result, acceptable use policies can act as a disincentive for independent researchers who red team models for issues related to safety and trustworthiness, which led over 350 researchers and advocates to sign an open letter calling for a safe harbor for this type of research.

The enforceability of acceptable use policies, especially for open foundation model developers, is a major limitation on how effective they are at restricting use. For example, the legality of enforcement actions based on the use restrictions contained in Responsible AI Licenses has not been tested, and in the current ecosystem there are few people who will be paid to enforce the terms of these licenses.9 Even if enforcement were simple, it may require developers to monitor users closely, which could facilitate privacy violations in the absence of adequate data protection, or increase the number of false refusals, reducing the helpfulness of foundation models.10

On the other hand, use restrictions in model licenses can have a dissuasive effect regardless of enforcement.11 Most companies and individual users are not bad actors and may adhere to a clear acceptable use policy despite gaps in enforcement. Acceptable use policies can play a helpful role in limiting undesirable uses of foundation models, though they are not without costs and limitations.

Government policies related to acceptable use policies for foundation models:

Governments have taken an interest in acceptable use policies, which are a salient effort by foundation model developers to “self-regulate.” The European Union’s AI Act requires that all providers of general-purpose AI models disclose the “acceptable use policies [that are] applicable” to both the EU’s AI Office and other firms that integrate the general-purpose AI model into their own AI systems.12 China’s Interim Measures for the Management of Generative Artificial Intelligence Services, which were adopted in July 2023, go a step further by requiring that providers of generative AI services act to prevent users from “using generative AI services to engage in illegal activities…including [by issuing] warnings, limiting functions, and suspending or concluding the provision of services.”13 In the US, the White House’s Voluntary AI Commitments, which 16 leading AI companies have adopted, include a provision that companies will publicly report “domains of appropriate and inappropriate use” as well as any limitations of the model that affect these domains.14

Neither the AI Act nor the White House Voluntary Commitments require that companies enforce their acceptable use policies or restrict any particular uses. While China’s Interim Measures for the Management of Generative Artificial Intelligence Services do not detail restrictions on content that is not outright illegal, regulatory guidance issued in February 2024 by China’s National Cybersecurity Standardisation Technical Committee specifies many types of prohibited uses such as subverting state power, harming national security, and disinformation.15

Acceptable Use Policies for Foundation Models in Practice

An overview of foundation model developers’ acceptable use policies:

Figure 2 details the acceptable use policies for 30 foundation model developers, including (i) the title of the acceptable use policy, (ii) whether it is applied to a specific foundation model, (iii) whether it is included in a model’s license, the company’s terms of service, or a standalone document, (iv) the developers’ flagship model series (and its modality), (v) the location of the developer’s headquarters, (vi) whether the weights of the developer’s flagship model series are openly available, and (vii) a reference to the public document that includes the acceptable use policy.16

Developers use different policy documents to restrict model use. These different types of documents include: standalone acceptable use policies for all of their foundation models (e.g., Google, Stability AI), use restrictions that are built into a general model license (e.g., AI2), use restrictions that are part of a custom model license (e.g., BigScience, Meta, TII), or provisions in an organization’s terms of service that apply to all services including foundation models (e.g., MidJourney, Perplexity, Eleven Labs). Developers release little information about how they enforce their acceptable use policies, making it difficult to assess whether one of these approaches is more viable.

Foundation model developers that have acceptable use policies are heterogenous along multiple axes. In terms of model release, 12 of the developers openly release the model weights for their flagship model series, while 18 do not. These models have a variety of different output modalities, with 19 language models, 5 multimodal models, 3 image models, 2 video models and 1 audio model. And in terms of where the developers are headquartered, 19 are based in the United States while the remainder include organizations are based in Canada, China, France, Germany, Israel, and the UAE. The different legal jurisdictions in which these organizations operate and make their models available helps explain some of the differences in the substance of their policies as some governments have requirements related to acceptable use policies and specific types of unacceptable uses.

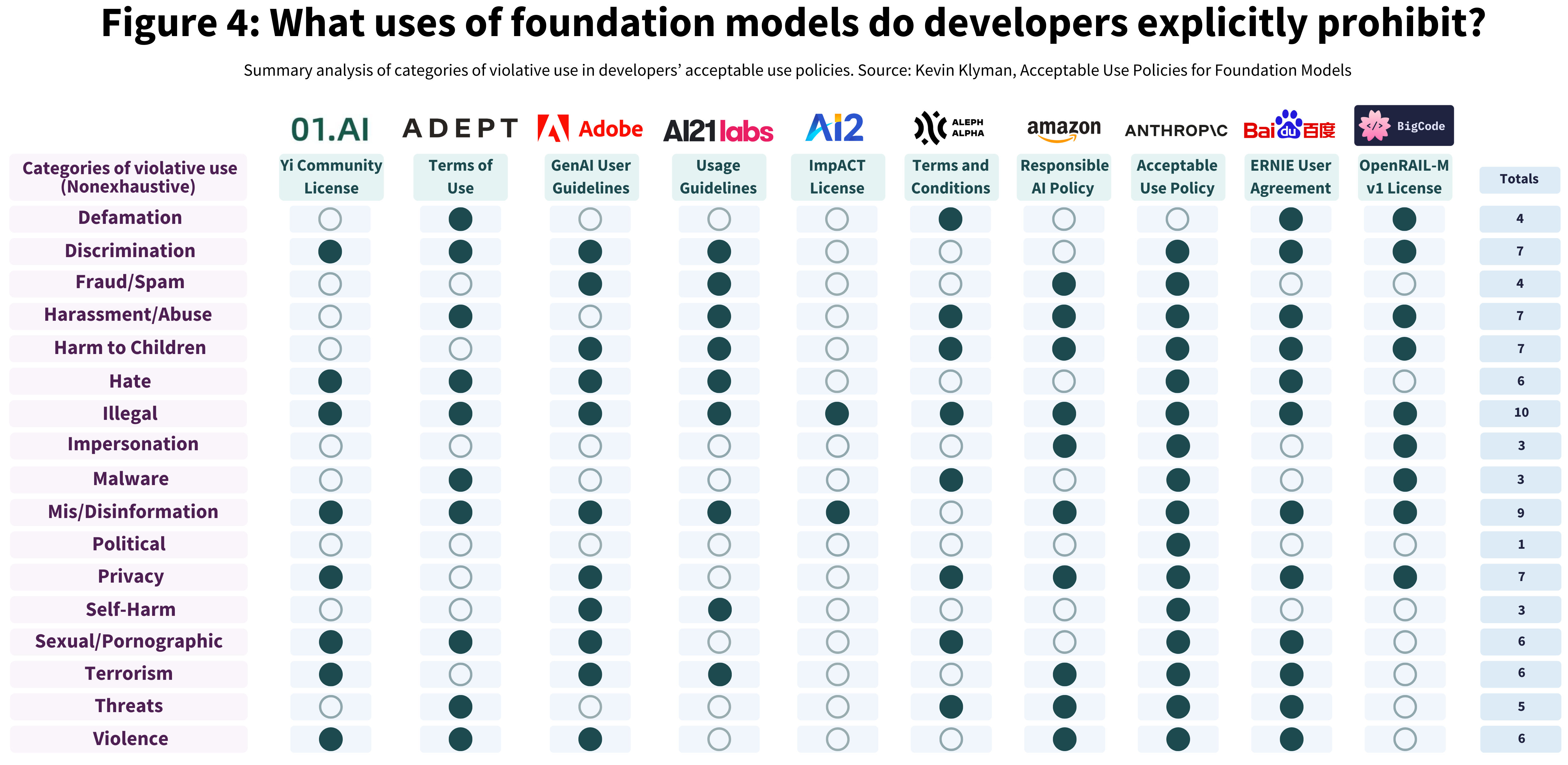

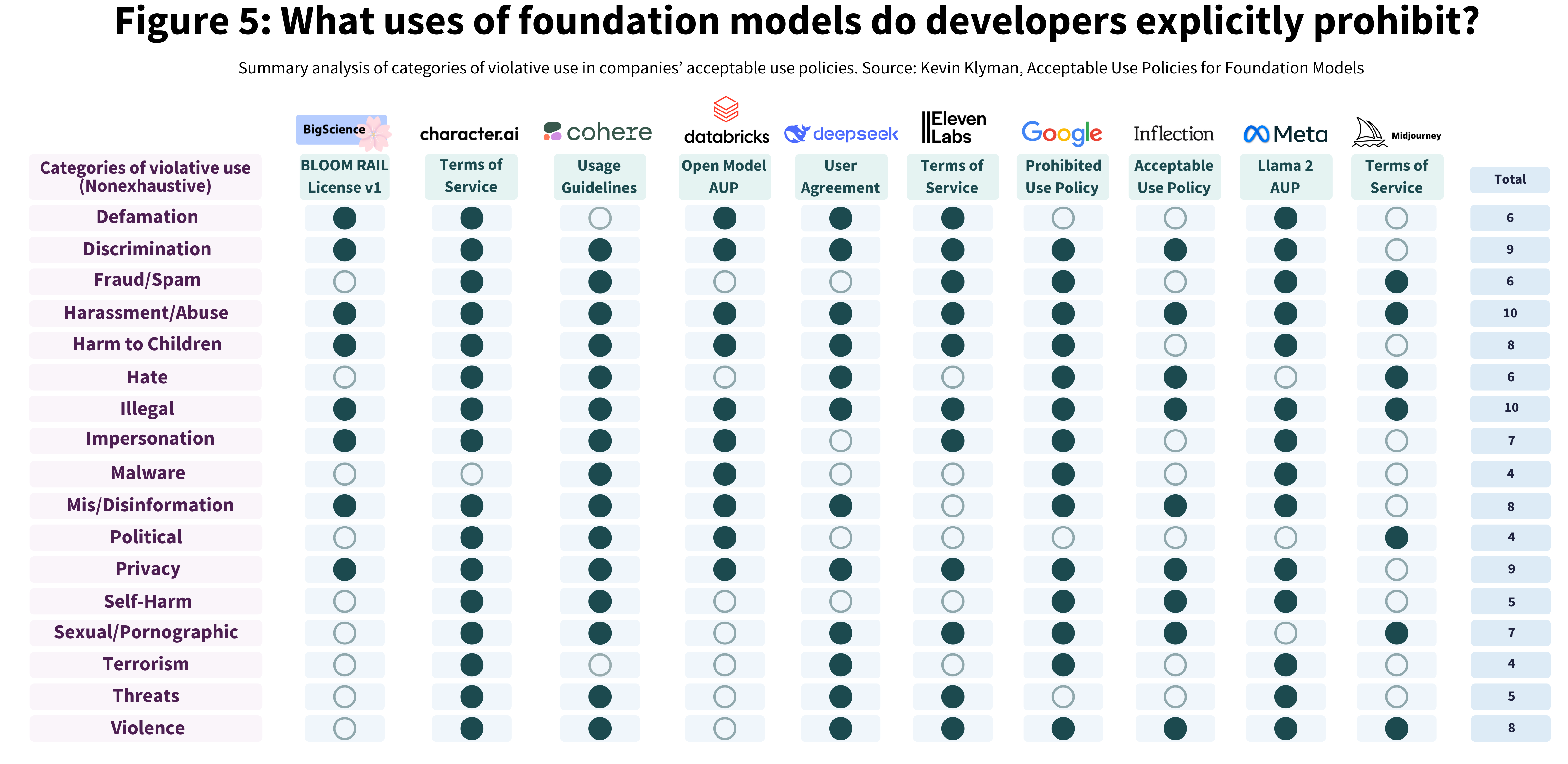

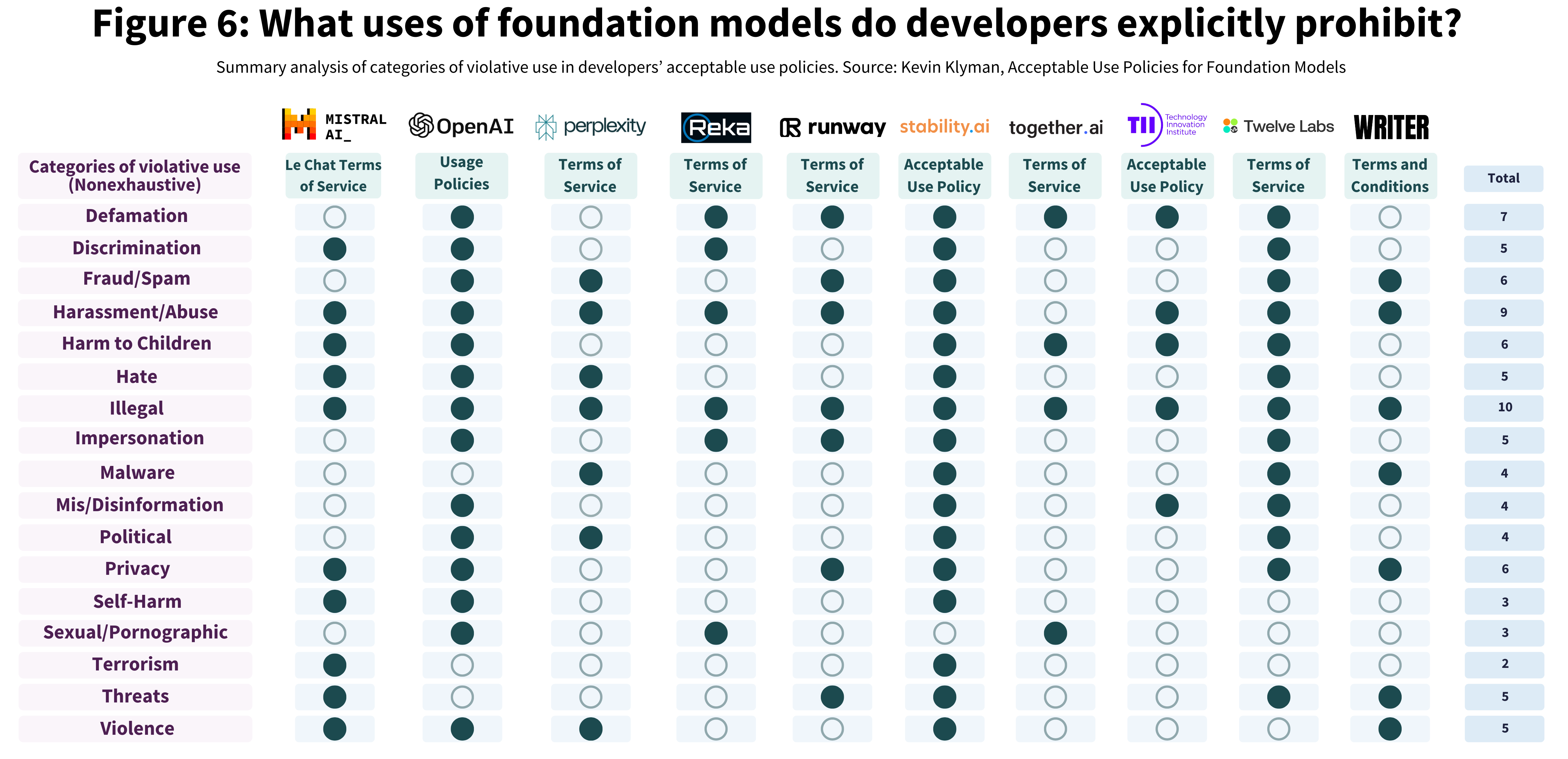

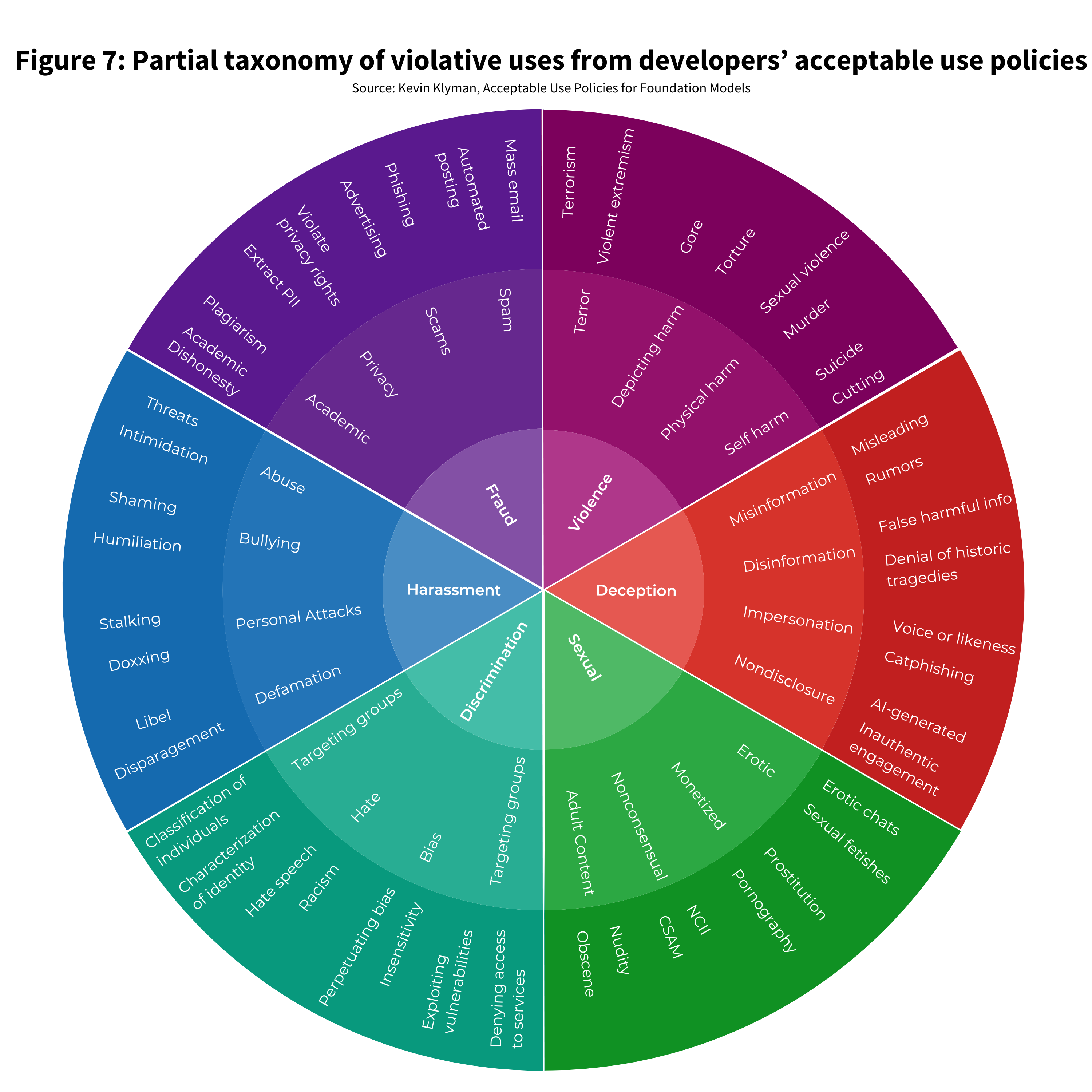

Content-based prohibitions17

Acceptable use policies commonly prohibit users from employing foundation models to generate content that is explicit (e.g., violence, pornography), fraudulent (scams, spam), abusive (harassment, hate speech), deceptive (disinformation, impersonation), or otherwise harmful (malware, privacy infringements).18 Many developers have granular restrictions related to these types of prohibited content (e.g., Anthropic, Cohere, OpenAI), whereas others have broad restrictions without much elaboration (e.g., AI21 Labs, Midjourney, Writer). Another group of developers has fairly minimal acceptable use policies, such as open developers like the Technology Innovation Institute, which prohibits use of Falcon 180B to harm minors, disseminate disinformation, or harass others; by contrast, Stability AI, another open developer, has over 45 itemized prohibited uses.19

Acceptable use policies also generally prohibit users from generating content that violates the law, impedes the model developer’s operations, or is not accompanied by adequate disclosure that it is machine-generated. These catch-all prohibitions cover unenumerated content that may be problematic, and make acceptable use policies more malleable and comprehensive by linking them to laws that may change. Importantly, content-based restrictions generally apply only to user prompts that attempt to have a model generate this type of content – models will classify the toxicity of this type of content if asked, but they will not generate it.

While the bulk of these prohibited uses are common across acceptable use policies, there are also a handful of edge cases.20 (See the underlying data in the GitHub.) Political content, such as using foundation models for campaigning or lobbying, is explicitly prohibited by OpenAI, Anthropic, Cohere, Midjourney, and others, whereas Google, Meta, and Eleven Labs have no such prohibition.21 Eating disorder-related content, such as prompts related to anorexia, is explicitly prohibited by Character, Cohere, Meta, and Mistral, but not by other developers. Weapons-related content is explicitly prohibited by the Allen Institute for AI, Anthropic, Meta, Mistral, OpenAI, and Stability, but not by other developers. And while some open developers such as Adept, DeepSeek, and Together broadly prohibit some types of sexual content, others like Meta and Mistral prohibit content related to prostitution or sexual violence.22

Several other prohibited uses that stand out include:

- Undermining the interests of the state: Baidu and DeepSeek, two of three model developers based in China in Figure 2, state in their acceptable use policies that users must not generate content “endangering national security, leaking state secrets, subverting state power, overthrowing the socialist system, and undermining national unity…damaging the honor and interests of the state…undermining the state’s religious policy”. 01.ai, the other Chinese developer, also includes a prohibition against “harming national security”. These restrictions directly parallel China’s regulatory guidance on Basic Safety Requirements for Generative Artificial Intelligence Services.

- Password trafficking: Eleven Labs, the only foundation model developer specializing in audio in Figure 2, prohibits users from using its models to “trick or mislead us or other users, especially in an attempt to learn sensitive account information, for example user passwords”. This may help address common concerns regarding the use of voice cloning for scams.

- Misinformation: The extent to which companies restrict users’ ability to generate inaccurate content varies widely. While some companies’ usage policies include wholesale bans on misinformation (e.g., AI21 Labs, Inflection), others have more lenient restrictions that apply only to verifiable disinformation with the intent to cause harm (e.g., TII).

Restrictions on types of end use:

In addition to content-based restrictions, acceptable use policies for foundation models often restrict the types of activities that users can engage in when using their models. Several notable examples include:

- Model scraping: Anthropic’s Acceptable Use Policy states that it does not allow users to “Utilize prompts and results to train an AI model (e.g., ‘model scraping’)”. Developers such as Adobe, Aleph Alpha, and Perplexity similarly prohibit the use of outputs of their models for training other foundation models.23

- Scaling distribution of AI-generated content: AI21 Labs’ Usage Guidelines state that “No content generated by AI21 Studio will be posted automatically (without human intervention) to any public website or platform where it may be viewed by an audience greater than 100 people.”

- Hosting the model with an API: The Technology Innovation Institute’s license for Falcon 180B, which incorporates its acceptable use policy, prohibits users from hosting the model with an API.24

⠀

Restrictions on industry-specific uses:

A number of acceptable use policies include restrictions that prevent firms in certain industries from making use of the related foundation models.25 Nevertheless, companies in these industries may succeed in using foundation models by negotiating permissive contracts with the developer. This creates an information asymmetry where the company and its clients are aware of the domains in which foundation models are being used, while regulators and the public may be led to believe that model use is based solely on the publicly disclosed acceptable use policy.

Common examples include restrictions on the following industries:

- Weapons manufacturers: Several acceptable use policies prohibit the use of models for the development of weapons, with some developers’ policies restricting many different specific types of weapons. Although the use of these foundation models by weapons manufacturers would violate the developers’ publicly stated acceptable use policy, it is possible that developers negotiate custom contracts with weapons manufacturers.

- Legal, medical, and financial advice: 8 of the 30 acceptable use policies prohibit users from leveraging foundation models for use in highly-regulated industries, such as providing legal, medical, and financial advice. This prohibition applies not only to lawyers, doctors, and financial advisers, but also to the many organizations that provide informal advice in these fields.

- Surveillance: The Allen Institute for AI, Anthropic, Amazon, Google, and OpenAI prohibit use of their models for surveillance to some extent. For instance, Google prohibits use of its models for “tracking or monitoring people without their consent” while AI2 singles out “military surveillance.” This would theoretically prevent spyware companies and defense and intelligence contractors respectively from making use of such foundation models.

⠀

Foundation models without acceptable use policies:

There are tens of foundation model developers besides the 30 described above and many do not have acceptable use policies for their models.26

Some open foundation model developers do not use acceptable use policies because their models are intended for research purposes only—if they were to adopt use restrictions, it could deter researchers from conducting safety research through red teaming, adversarial attacks, or other means (in the absence of an exemption for research). Other models intended for research may lack acceptable use policies on the basis that they present less severe risks of misuse, whether because they have less significant capabilities or fewer users.27 Non-commercial models such as these are frequently distributed using licenses without use restrictions such as Apache 2.0 or Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial licenses. While a model may not include any use restrictions for noncommercial users, commercial users may have to agree to custom use restrictions in their contracts with the model developer.

Models for commercial use may not include acceptable use policies for several reasons.28 In some cases, models are not intended for commercial use without further fine tuning or other safety guardrails, leading developers to offer the model as is, leaving downstream developers to restrict uses (e.g., Databricks’ MPT-30B). Other developers release their models without complete documentation, whether because they intend to release an acceptable use policy at a later point, which could be part of staged release, or due to under-documentation in the rush to release a model.

Nevertheless, foundation models without acceptable use policies may be covered by other kinds of restrictions. Alibaba Cloud restricts companies with over 100 million users from making use of Qwen-VL through its license, which also bans model scraping. Restrictions on who can use a foundation model may have a significant effect on how it is used even in the absence of binding restrictions on certain categories of use.

Discussion:

Governments have attempted to spur self-regulation in the foundation model ecosystem through voluntary codes of conduct.29 The G7 and member states such as the US and Canada have issued codes of conduct and received pledges from leading foundation model developers. The G7’s code of conduct states that foundation model developers should “take appropriate measures… [to] mitigate risks across the AI lifecycle” including risks related to bias, disinformation, privacy, and cyber. Canada’s code of conduct requires developers to create “safeguards against malicious use” while the White House’s “Voluntary AI Commitments” include a commitment to “prioritize research on societal risks posed by AI systems” such as risks to children.

However, these codes of conduct stop short of recommending that foundation model developers enact binding restrictions on risky use cases. Foundation model developers have gone beyond voluntary commitments, shielding themselves against legal liability for misuse of their models. In this way, acceptable use policies are a significant form of self-regulation.

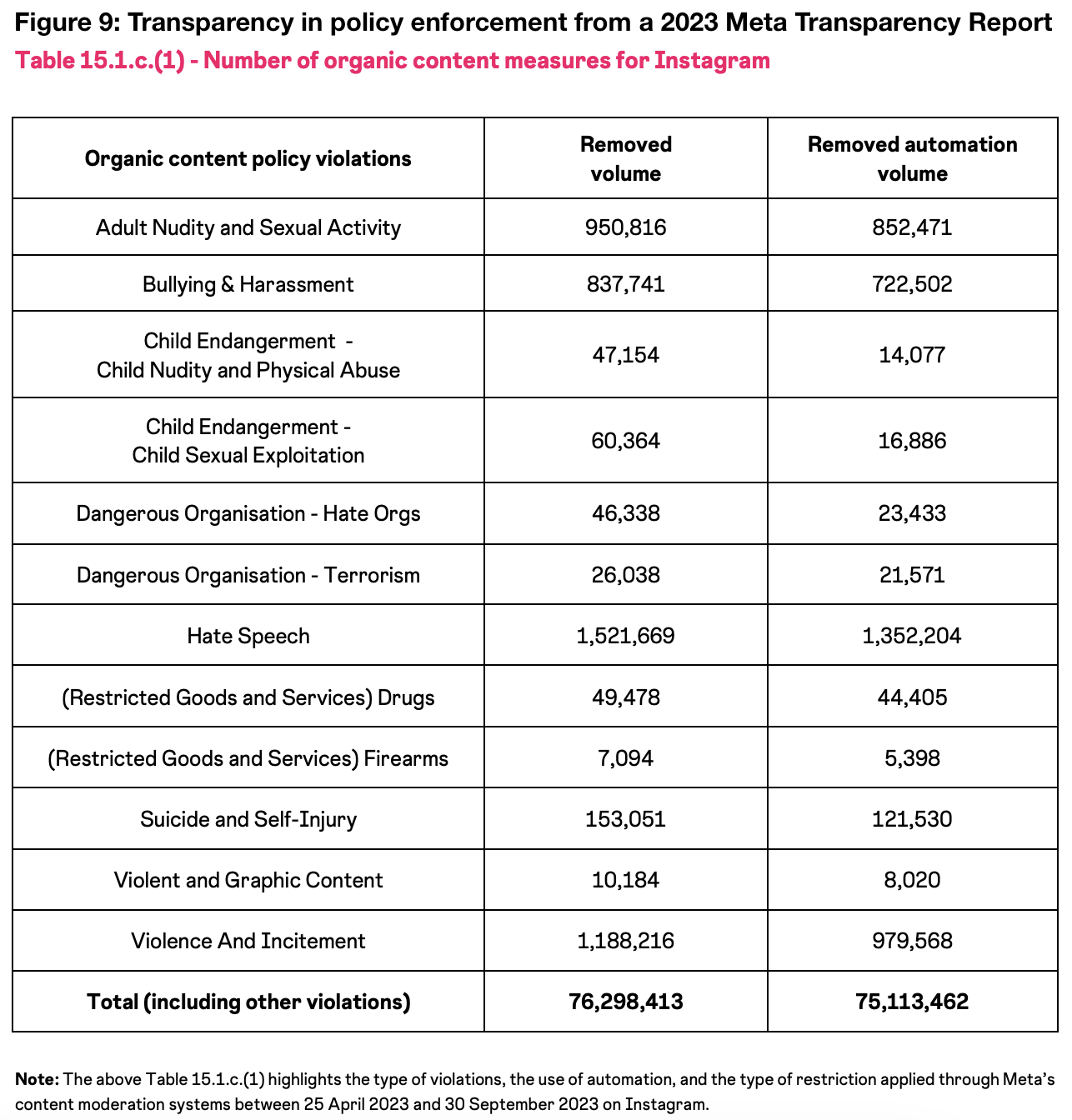

Still, there is little publicly available information about how acceptable use policies are actually enforced. Although companies make the prohibited uses of their models clear, it is often unclear how they enforce their policies against users. Just as the 2023 Foundation Model Transparency Index found that 10 leading foundation model developers share little information about how they enforce, justify, and provide appeals processes for acceptable use policy violations, this work finds that other foundation model developers provide little or no information about these matters. This lack of transparency is different from other digital technologies; social media companies, for instance, regularly release transparency reports that provide details about how they enforce their acceptable use policies and other provisions in their terms of service. Without information about how acceptable use policies are enforced, it is not obvious that they are actually being implemented or effective in limiting dangerous uses. Companies are moving quickly to deploy their models and may in practice invest little in establishing and maintaining the trust and safety teams required to enforce their policies to limit risky uses.

Another issue in gauging the enforcement of acceptable use policies is the way in which they propagate across the foundation model ecosystems. Companies’ publicly available policies often do not specify precisely how their acceptable use policies propagate to third parties such as cloud service providers, and whether third parties have obligations to enforce the original acceptable use policy. In addition to developers, cloud service providers act as deployers of foundation models that were not developed in-house. Cloud service providers have their own acceptable use policies that do not align perfectly with external developers’ acceptable use policies, and it is not clear that a cloud provider would have adequate expertise to restrict the uses of the foundation models in accordance with acceptable use policies that are more stringent than that of the cloud provider.30

Acceptable use policies may impose obligations on users that they are ill equipped to follow. Acceptable use policies are a means of distributing responsibility for harm to users and downstream developers; however, these other actors may not be well suited to prevent certain uses of a developer’s model.31 Restricting users from generating self-harm related content, for instance, only works for some types of users—for example, vulnerable users who are turning to a language model for advice may trigger acceptable use policies by openly sharing their mental health issues.

Questions regarding the enforceability of acceptable use policies extend beyond users who cannot self-enforce. While many acceptable use policies are reasonably comprehensive, the degree to which developers can enforce their policies differs across context and jurisdiction. Enforcement of acceptable use policies differs based on how models are deployed, whether through an API, a user interface operated by the developer, or locally. Strict enforcement is near impossible when models are deployed locally, whereas it resembles content moderation for social media platforms when models are deployed via an API.

Nevertheless, many open foundation model developers attempt to restrict the use of their models to some degree. Twelve of the developers examined that have acceptable use policies openly release their model weights (and other assets in some cases), but do so using licenses or terms of service that block certain unacceptable uses. Although open foundation models are frequently referred to as “open-source” in popular media, truly open-source software or machine learning models cannot have use restrictions by definition.

While many previous works have taxonomized the risks stemming from foundation models, this post assesses how companies taxonomize risk on the basis of their own policies. Future research directions include assessing the enforcement of acceptable use policies and comparing acceptable use policies to model behavior policies, toxicity classifiers, responsible scaling policies, and existing AI regulations.

Key takeaways for policymakers:

1. Developers’ acceptable use policies have important differences

Acceptable use policies differ across developers in terms of restrictions on content, types of end use, and industry-level restrictions. These differences have been underexplored and may have important implications for the safety of foundation model deployment.

- There are several gray areas where some companies include content-based restrictions and others do not. Content related to politics, eating disorders, sex, and medical advice are among the areas where some companies have harsh prohibitions and others are silent.

- While some companies’ policies prevent their models from being used by the weapons or surveillance industry, others have few industry-related restrictions, and others release only noncommercial models with no policies limiting use.

⠀ 2. Acceptable use policies help shape the foundation model market

Acceptable use policies alter the foundation model market by affecting who can use a model and for what purpose.

- Foundation model developers advertise use restrictions or lack thereof as a comparative advantage relative to other companies. For example, Mistral says its models are “customizable at will,” allowing users to adapt its models more fully, whereas OpenAI states it provides safety to users and the ecosystem through “post-deployment monitoring for patterns of misuse”.

- Foundation model developers employ acceptable use policies in order to prevent other companies from making use of their services, stealing their intellectual property, or using their products to develop a competitor.32 For example, companies ban firms and other users from using their models to train other AI models, restricting the supply of datasets of model outputs and concentrating the market for models that are trained on model outputs.33

- Acceptable use policies help determine what industries can make use of developers’ foundation models. For example, policies that prohibit the use of models for weapons production may block the arms industry from making use of those foundation models.

- Acceptable use policies determine the types of uses that are legitimate for foundation models (e.g., no automated decision systems). Even industries that are allowed to make use of models may not be able to do so for common applications.

⠀

3. Policy proposals to restrict the use of foundation models should take acceptable use policies into account

Many AI regulatory proposals do not acknowledge that companies already limit the use of their foundation models with acceptable use policies. Policymakers should craft regulations that contend with existing restrictions in these acceptable use policies, including by potentially reinforcing them or by helping to close gaps in enforcement regimes.

- Among the most common policy proposals related to foundation models are those that propose to restrict specific uses. Policies such as liability for model developers and export controls on model weights are primarily intended to block undesirable uses of foundation models.

- These policies should account for the fact that foundation model developers already have policies in place that prevent such risky uses. For example, every foundation model developer restricts unlawful uses, a broad restriction that governments could encourage developers to enforce in specific ways.

- Enforcement of acceptable use policies (and companies’ other policies) is piecemeal and quite difficult. Policymakers should encourage and assist in enforcement of existing policies in addition to imposing new requirements.

Acknowledgments

I thank Ahmed Ahmed, Rishi Bommasani, Peter Cihon, Carlos Muñoz Ferrandis, Peter Henderson, Aspen Hopkins, Sayash Kapoor, Percy Liang, Shayne Longpre, Aviya Skowron, Betty Xiong, and Yi Zeng for discussions on this topic. A special thanks to Loredana Fattorini for her assistance with the graphics.

@misc{klyman2024aups,

author = {Kevin Klyman},

title = {Acceptable Use Policies for Foundation Models: Considerations for Policymakers and Developers},

howpublished = {Stanford Center for Research on Foundation Models},

month = apr,

year = 2024,

url = {https://crfm.stanford.edu/2024/04/08/aups.html}

}

-

Acceptable use policies are given different names by developers, with some labeling them as prohibited use policies, use restrictions, usage policies, or usage guidelines. In this post, acceptable use policy is used as a catch-all term for any policy from a foundation model developer that restricts use of a foundation model. Use restrictions imposed by deployers of the foundation model, model hubs, and other actors in the AI supply chain are highly relevant to these issues but are outside the scope of this post. ↩

-

While many companies choose to release acceptable use policies as standalone documents, they are then invoked in the terms of service. ↩

-

OpenAI’s Usage Policies state “We also work to make our models safer and more useful, by training them to refuse harmful instructions and reduce their tendency to produce harmful content.” ↩

-

Developers often refer to model behavior policies as “model policies.” For example, Google’s technical report for Gemini states “We have developed a set of model safety policies for Gemini models to steer development and evaluation. The model policy definitions act as a standardized criteria and prioritization schema for responsible development and define the categories against which we measure launch readiness. Google products that use Gemini models, like our conversational AI service Gemini and Cloud Vertex API, further implement our standard product policy framework which is based on Google’s extensive experience with harm mitigation and rigorous research. These policies take product use cases into account – for example, providing additional safety coverage for users under 18.” ↩

-

In order to make use-based licensing more stringent, developers might adopt model licenses that prohibit uses that are deemed out-of-scope by the model card. ↩

-

There is some overlap between API policies and acceptable use policies; some companies apply acceptable use policies to all of their services (including their APIs) whereas others have separate policies for models, systems, products, and APIs. Many companies do not offer APIs and so do not have API policies. ↩

-

As one example, users of Amazon Bedrock must agree to an end-user license agreement in order to gain access to each foundation model on the platform. These agreements are custom terms of service agreements for the use of the foundation model via Amazon Bedrock and often reference the developer’s acceptable use policy (they can be found on the Model Access page). ↩

-

The full section reads, “Prohibit misuse: Publish usage guidelines and terms of use of LLMs in a way that prohibits material harm to individuals, communities, and society such as through spam, fraud, or astroturfing. Usage guidelines should also specify domains where LLM use requires extra scrutiny and prohibit high-risk use-cases that aren’t appropriate, such as classifying people based on protected characteristics. Build systems and infrastructure to enforce usage guidelines. This may include rate limits, content filtering, application approval prior to production access, monitoring for anomalous activity, and other mitigations.” ↩

-

There is a growing academic literature and wider discussion in the AI research community regarding the purpose, prevalence, and enforceability of Responsible AI Licenses for open model developers. Many of the open foundation model developers discussed in this post draw on Responsible AI Licenses with identical or near-identical terms, including BigCode, BigScience, and Databricks. (Character AI’s terms of service also state that “your use of the Services may be subject to license and use restrictions set forth in the CreativeML Open RAIL-M License,” while Google’s prohibited use policy for its Gemma models bears some resemblance to OpenRAIL licenses.) Closed foundation model developers have also drawn on each other’s policies, with many using language similar to OpenAI’s usage policy (which was among the first such policies). ↩

-

There are also a wide variety of use cases for foundation models that could be beneficial but are prohibited by major developers’ acceptable use policies. For example, organizations that seek to use foundation models to engage in harm reduction regarding prohibited categories of harm would not be able to do so under such acceptable use policies. ↩

-

Firms may be more risk averse and enforcement of acceptable use policies against corporate users can be more straightforward. Moreover, there are benefits to Responsible AI Licenses that should be considered alongside enforcement challenges. For example, BigCode’s OpenRAIL-M license requires that downstream developers share existing model cards and add additional high-quality documentation to reflect changes they make to the original model, which could help improve transparency in the AI ecosystem. ↩

-

The definition of providers of generative AI services includes foundation model developers providing their models through an API or other means. See Article 14 and Article 22(2) of the Interim Measures for the Management of Generative Artificial Intelligence Services. ↩

-

The Hiroshima Process International Code of Conduct for Organizations Developing Advanced AI Systems, which was published by the G7, also requires that companies publicly report domains of appropriate and inappropriate use. The signatories to the US voluntary commitments are Amazon, Anthropic, Google, Inflection, Meta, Microsoft, and OpenAI, which signed in July 2023, and Adobe, Cohere, IBM, Nvidia, Palantir, Salesforce, Scale AI, and Stability AI, which signed in September 2023. ↩

-

See Appendix A on Main Safety Risks of Corpora and Generated Content in China’s National Cybersecurity Standardisation Technical Committee’s Basic Safety Requirements for Generative Artificial Intelligence Services. ↩

-

(1) Note: not all of these policies are directly comparable or comprehensive. Some companies have many additional provisions in their terms of service for various products, platforms, and services that may include additional use restrictions. For example, the “Meta AIs Terms of Service” covers use of Meta’s foundation models on its own platforms; DeepSeek has a license for its flagship model with use restrictions; and Google has thousands of different terms of service agreements. Companies with general acceptable use policies often also have model-specific acceptable use policies with additional use restrictions, though these are outside the scope of this post. (2) The acceptable use policies cited here are (i) specifically applied to foundation models by the developer (i.e. they are invoked for a specific foundation model, the contract that includes them cites their applicability to the developer’s AI models, or the licensor’s primary product is a foundation model so a plaintext reading of a contract that applies to all products and services is sufficiently tied to a foundation model), (ii) name prohibited types of content (i.e. acceptable use policies that are content neutral are excluded), and (iii) are incorporated into the license or terms of service to make them binding. (3) Luminous’ model weights are open for customers, but not the general public. (4) AWS’ Responsible AI Policy points directly to AWS’ acceptable use policy in the text, so I consider both for the purposes of this post; the same is true of Mistal’s terms of use and its terms of service for Le Chat. (5) As a whole, acceptable use policies change with some frequency—as one indication of this, multiple policies changed significantly over the course of writing this post. ↩

-

For a full list of content-based prohibitions in companies’ acceptable use policies, see the GitHub. The repo also has details on how figures 3-6 were compiled. ↩

-

Use restrictions in a developer’s acceptable use policy vary by the modality of its models. For example, acceptable use policies for image models have less need to restrict the generation of malware than those for language models. ↩

-

Minimalist acceptable use policies are not necessarily less forceful. The Allen Institute for AI, for example, is the only developer whose acceptable use policy singles out uses related to military surveillance and has strong terms regarding “‘real time’ remote biometric processing or identification systems in publicly accessible spaces for the purpose of law enforcement”. ↩

-

Note: this analysis is based on uses that are referenced explicitly in developers’ acceptable use policies—there are many similar prohibited uses that are described with slightly different language and so are not accounted for here. This exercise is, to a significant degree, an effort to capture the language that developers use to taxonomize and describe unacceptable uses. ↩

-

Stability AI strikes a middle ground here, prohibiting “Generating or facilitating large-scale political advertisements, propaganda, or influence campaigns”. ↩

-

Meta does have a narrow prohibition on “the illegal distribution of information or materials to minors, including obscene materials,” as does Stability AI. However, the lack of broader restrictions on sexual content implies that downstream developers that fine tune Llama 2 to produce sexual chatbots may not be violating its acceptable use policy. AI pornography sites like CrushOn (which claims to use Llama 13B Uncensored – a fine-tuned version of Llama, not Llama 2) and SpicyChat (which claims to use Pygmalion 7B, another fine-tuned version of Llama) may be within their rights to use Llama 2 in the future for use cases that other developers prohibit. ↩

-

OpenAI’s Business Terms do not allow other businesses “to develop any artificial intelligence models that compete with our products and services,” which reportedly led it tosuspend ByteDance’s account. There have also been other reports of model developers enforcing related terms on other companies. ↩

-

Section 9.3 of the Falcon 180B license reads “you are not licensed to use the Work or Derivative Work under this license for Hosting Use. Where You wish to make Hosting Use of Falcon 180B or any Work or Derivative Work, You must apply to TII for permission to make Hosting Use of that Work in writing via the Hosting Application Address, providing such information as may be required” where Hosting Use “means any use of the Work or a Derivative Work to offer shared instances or managed services based on the Work, any Derivative Work (including fine-tuned versions of a Work or Derivative Work) to third party users in an inference or finetuning API form.” ↩

-

References in acceptable use policies to unsolicited advertising, gambling, prostitution, and multi-level marketing schemes also function as restrictions on specific industries. ↩

-

Stanford CRFM’s Ecosystem Graphs documents over 75 different developers of foundation models. ↩

-

Another view is that acceptable use policies are inappropriate for foundation models and should instead apply to AI systems that incorporate foundation models. ↩

-

Note: Phi-2 was originally released under a Microsoft Research license, not an MIT license. Phi-2’s page on Hugging Face also features the Microsoft Open Source Code of Conduct. ↩

-

Voluntary codes of conduct from the G7 and U.S. explicitly call out foundation models, while Canada refers to generative AI systems with general-purpose capabilities. The G7 states “the Hiroshima Process International Code of Conduct for Organizations Developing Advanced AI Systems aims to promote safe, secure, and trustworthy AI worldwide and will provide voluntary guidance for actions by organizations developing the most advanced AI systems, including the most advanced foundation models and generative AI systems”. The White House states “The following is a list of commitments that companies are making to promote the safe, secure, and transparent development and use of generative AI (foundation) model technology.” ↩

-

Model hosting platforms such as Hugging Face and GitHub also have policies regarding the types of content they will host that may overlap with developers’ acceptable use policies. ↩

-

Many developers’ terms of service make clear that users are fully responsible for how they use the developer’s foundation models. For example, Reka AI’s terms read “You are solely responsible for your use of your Outputs created through the Services, and you assume all risks associated with your use of your Outputs, including any potential copyright infringement claims from third parties”. ↩

-

Foundation model developers may limit use of their models in order to ensure that use restrictions on some training datasets (e.g., related to copyright, trademark, and protected health data) are honored. ↩

-

User restrictions have a significant effect here as well. Companies that restrict competitors (or companies with a large number of users) from making use of their models have taken a major step in restricting model use. ↩