Co-Composition with an Anticipatory Music Transformer

Authors: John Thickstun and Carol Reiley and Percy Liang

Featured performers: In Sun Jang (violin) and John Wilson (piano).

Generative models offer exciting new tools and processes for artistic work. This post describes the use of a generative model of music—the Anticipatory Music Transformer—to create a new musical experience. We used the model to compose a violin accompaniment to Beethoven’s Für Elise. On a technical level, this demonstrates the Anticipatory model’s ability to complement and adapt to a pre-existing composition. Artistically, we find that the accompaniment encourages the audience to listen to the familiar phrases of Für Elise with fresh ears. This composition was premiered by In Sun Jang (violin) and John Wilson (piano) for Carol Reiley and the Robots: a San Francisco Symphony SoundBox event on April 5th and 6th, 2024.

This genesis for this work was the opportunity to premier a machine-assisted music composition with performers from the San Francisco Symphony at a SoundBox event at Davies Symphony Hall. Ticket-holders voted to hear a composition derived from Beethoven’s Für Elise. We decided that this derived composition would take the form of a violin accompaniment using a human editorial process described in detail below. Generating this accompaniment highlights a co-creative capability of the Anticipatory Music Transformer that has been underexplored in previous human-AI collaborations.

Music exists in two distinct media: the symbolic medium of musical compositions, and the acoustic medium of musical performances. While recent commercial work on music generation focuses on the acoustic medium (e.g., Suno, Udio) we work in the symbolic medium. Symbolic generative models afford a composer greater control over inputs and outputs (as we will see below) and by generating a musical score we give accomplished musicians the opportunity to breathe another layer of interpretation and life into a live performance.

Co-composition with an Anticipatory Music Transformer

Prompting the Model

We prompt the model to generate a violin accompaniment by explicitly writing down a single violin note early in the composition. This encourages the model to generate a continuation of the composition that includes a violin part. The timing of the note instructs the model when the accompaniment should begin; and the duration of the note influences the style of the subsequent violin content generated by the model.

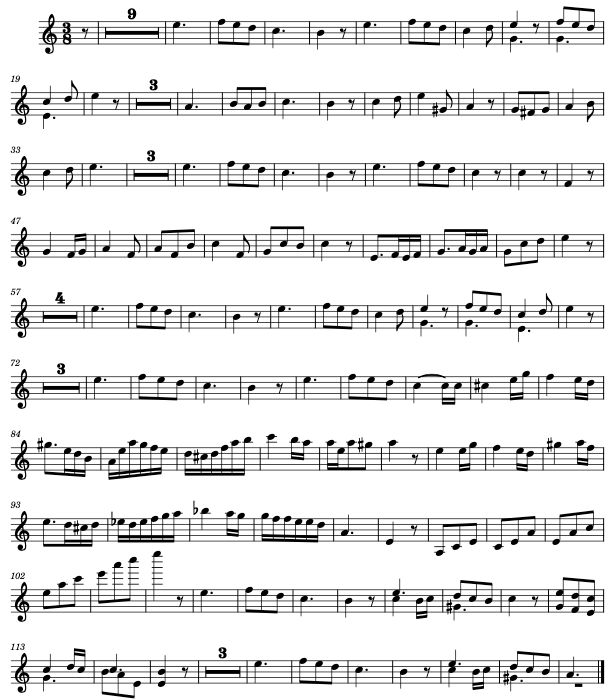

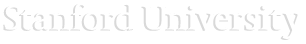

Figures 2 and 3 illustrate two accompaniments generated by the model, based on different single-note prompts. We could provide a longer prompt, exerting more influence over the generated composition, but in this work we elected for a minimal prompt allowing the model greater freedom over its output. Even prompting with a single note, we see how much the generated composition can change, based on the time-placement of the prompt note and its duration.

After some initial experimentation, we elected to prompt the model starting from the beginning of the second full phrase of Für Elise (10 bars into the composition) with a dotted-quarter note. We found that prompting with a longer-duration note (i.e., a dotted-quarter note) tends to produce sparser violin accompaniments, which we found to be more aesthetically pleasing than a more dense layer of violin notes on top of the already fully-formed composition of Für Elise.

Editorial Control

We see generative models as tools for complementing and augmenting human creativity; we are interested in co-creative, interactive experiences with these models, rather than a fully automated process. In this spirit, we composed the accompaniment to Für Elise using the Anticipatory Music Transformer as a sophisticated autocompletion tool. We broke Für Elise down into 17 sub-phrase of approximately 8 bars in length, delimited by “waypoints.” For each phrase, we prompted the model to suggest continuations of the next phrase, repeating the prompt until the model proposed a continuation that we liked. We kept a record of these interactions with the model, recorded in Table 1.

| Waypoint | Time Range | Description | Rejected Candidates |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.0-11.5 | initial theme | (no accompaniment) |

| 2 & 3 | 11.5-29.0 | theme repeats | (no record) |

| 4 | 29.0-37.75 | theme repeats | 8 |

| 5 | 37.75-46.5 | subphrase | 5 |

| 6 | 46.5-55.25 | theme repeats | 2 |

| 7 | 55.25-64.0 | variation | 11 |

| 8 | 64-75.25 | subphrase | 15 |

| 9 | 75.25-84.0 | main theme | 3 |

| 10 | 84.0-92.75 | subphrase | 0 |

| 11 | 92.75-100.25 | theme repeats | 2 |

| 12 | 100.25-110.25 | variation | 18 |

| 13 | 110.25-122.75 | subphrase | 30 |

| 14 | 122.75-130.25 | "bridge" | 15 |

| 15 | 130.25-139.0 | main theme | 2 |

| 16 | 139.0-147.75 | theme repeats | 15 |

| 17 | 147.75-156 | end | 4 |

Following the piano introduction (Waypoint 1) and the initial violin theme in (Waypoint 2-3) that we selected from an earlier set of interactions with the model, at each subsequent Waypoint we queried the model to generate the next section of the violin accompaniment. In most cases, we rejected the first candidate proposed by the model. Our reasons for rejecting a proposed continuation fell into the following categories:

- Repetition. The model repeated the same simple theme over and over again.

- Sparsity. Sometimes the model would stop generating violin notes, or degenerate into just playing the root of a chord on downbeats.

- Density. Mindful of the criticism of the early violin accompaniments, I tried to avoid particularly dense counterpoint.

- Mimicry. Sometimes the model decides to duplicate a line of the piano part in unison, which seemed not particularly interesting.

Notes on our composition process show that we searched through 8 candidates at Waypoint 4 to find an interesting continuation that didn’t simply repeat the theme established in Waypoint 2. We searched through many candidates in Waypoints 6-7 and in Watpoints 11-13. In each of these cases, the piano part introduces new thematic material with a high density of notes; in these scenarios the model was much more likely to produce outputs that we deemed undesirable. We also looked at a significant number of candidates at Waypoint 15, searching for a satisfying conclusion to the composition. Finally, a behavior that often led us to reject a candidates (not associated with any particular waypoint) was proposed violin continuations that mimicked the piano part: an example of mimicry is illustrated by Figure 4.

Many of the editorial decisions involved in creating the final violin accompaniment were objective: choosing a better candidate proposal over a worse one. As generative models of music improve, we expect that the human decisions involved in these processes will become more an expression of artistic vision and taste, rather than a quality-control mechanism.

Exploring a Branching Tree of Variations

Autoregressive generative models like the Anticipatory Music Transformer generate music by iteratively predicting the next note in a time-ordered sequence. At each point in this sequence, the model makes a choice about what note should come next. This choice in turn affects each subsequent choice by the model, creating a near-infinite branching tree of compositional variations. See Example 1 to explore for yourself some alternative violin accompaniments, beginning from each waypoint. These continuations have been mildly-curated to exclude less interesting sparse or repetitive alternatives.

- Input (Für Elise)

- Output (Generated Violin)

The Premier Performance

This violin-accompaniment of Für Elise composed by the Anticipatory Music Transformer was premiered by In Sun Jang (violin) and John Wilson (piano) at the Carol Reiley and the Robots SoundBox event on April 5th and 6th, 2024. To visually indicate the machine-generated origin of the composition, violinist In Sun Jang was bathed in green light and notes of the violin composition were displayed in green on large screens above the stage.

The program notes for the performance stated that:

Download a complete audio recording of the performance: [mp3].

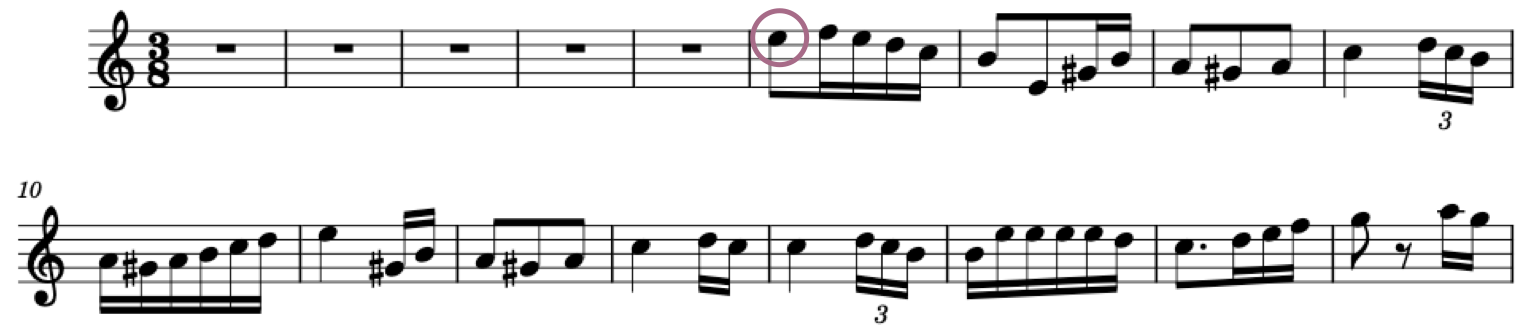

A Complete Synthesized Performance and Violin Score

Example 2 provides a complete synthesized performance of the violin-accompanied Für Elise; the score for the violin part is included in Figure 6. You can read more about the Anticipatory Music Transformer here.

- Input (Für Elise)

- Output (Generated Violin)